- Home

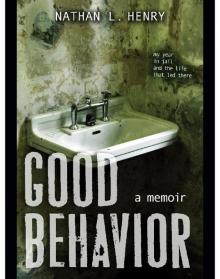

- Nathan L. Henry

Good Behavior Page 13

Good Behavior Read online

Page 13

“Yeah,” I said. “I’m here.” Everybody had known about it. Mom and Dad knew she might be pregnant. I had wanted her to be pregnant. I was excited. I told my brother that it felt like—get this—Christmas. Now, in my cell, I felt like such an idiot. A baby would have been the absolute last thing I needed.

“We should’ve fucking killed her,” Philip said. He was just going along with what he thought I might have been thinking. He did this a lot.

“Don’t say that,” I said. I remembered making love to her. I remembered her brown eyes. I remembered how I felt I couldn’t live without her. I was desperate with her.

“I heard her brother’s out to get you when you get out of there.”

I didn’t want to talk anymore. I didn’t want to hear about any idiotic drama. “Her brother’s a pussy,” I said dismissively.

“I know, but he’s talking shit all over the place.”

“I don’t care!” I was getting frustrated. “You think it is my kid?”

“I don’t know.”

“It could be anybody’s.” I meant it. It really could be anybody’s. But it could be mine too.

“It’s not mine,” he said. “I never fucked her.”

“I know, man.”

We hung up after a couple more awkward moments, and I went on thinking about Joan.

She was my first love affair. I was, in every sense of the word, entangled with her—it was really as if she were a part of me, and all that emotion, all that commitment was reciprocated—at least I believed it was. I didn’t stop believing it even after she drove away—I had my fears and my suspicions, but those are easy to brush aside. It all became unbearably obvious soon enough: I decided to travel halfway across the country to shoot her in the head.

[ FORTY-TWO ]

I was sixteen and fresh out of the nuthouse (Charinton) when I saw Joan for the first time—she wore combat boots and a black leather trench coat. She carried a copy of Freud’s Totem and Taboo as she walked into my fifth-period study hall. Her hair was a kind of neon blue with streaks of red in it. She sat in front of me.

“Psst. What are you reading?” I asked.

She held it up.

I showed her my Say You Love Satan.

She nodded approvingly.

I asked, “Are you into this?”

She said, “What, Satanism? Sure.”

I said, “Let’s get a smoke after study hall. I know where to go.”

So after study hall I took her to the spot around the east wall of the building where we couldn’t be seen. David was there, bitching about something or other, probably fretting over an imminent ass-whipping by some jock. Joan and I talked about Satanism, heavy metal music, and sex. I thought I had met my soul mate.

After school that night I saw Joan sitting down on one of the guardrails leading up to the bridge down the street from my house. She had her guitar with her, a little blue electric, and we jammed. I showed her some Metallica licks and she showed me some Guns N’ Roses licks. I was smitten.

Hanging out around the stoop under the Roll of Honor mural one night with a group of the hoods, I heard somebody asked Charlie Bender if he’d fuck Joan. He said, “Hell, no! She’s ugly as a fucking dog, man!”

“I know, man.” Rich Bass made a puking sound. “Nasty.”

I didn’t agree, but I thought it wise to keep my mouth shut. I was fairly ambivalent about what they were saying. On the one hand, no one wants a girlfriend everybody thinks is ugly, but on the other hand, it didn’t look like I had any competition, which was good. And after I did start dating her, nobody ever said another word about it.

Patty was calling me in the evenings, but I was losing interest. She revealed that she sang country music at honky-tonks on the weekends. This disgusted me. If she sang death metal, that would be one thing, but country? It was on Valentine’s Day that Joan came to my house for the first time. I hadn’t invited her. She just knocked on the door and we stood around on the sidewalk smoking and talking for a couple of hours.

A lot of time was spent on my stoop in those days. Mickey Bowen used to come by and jam with me. Eventually a crowd would gather. My dad distrusted the kids I hung out with and wouldn’t let them in the house, and rightfully so.

When Joan left that night and I went back inside, my mom said, “So who was the girl with the disturbing hair?”

“A friend,” I replied.

That night I broke up with Patty and asked Joan to be my woman.

[ FORTY-THREE ]

GED classes were available for the inmates at the jail. They took place once a week in the law library. Though I already had my GED, I took the classes just to get out of my cell for a little while. This was the only time I interacted face-to-face with the adult inmates—that is, without a door or window separating us.

Ed had a shaved head and tattoos, and he was pretty. I think he was a biker. He asked me one day, “You still in a cell with that old-lady killer?”

“No,” I said. “Haven’t been in a long time.”

“That little fucker do it?”

“I don’t know. He says he didn’t.”

“What’s your feeling?”

“I think maybe he did. I don’t know.”

He shook his head. “Fucking stupid.”

A black guy sat next to him; I think his name was Kimball. Now, he was hard. Kimball gave you the sense he’d been there and back, and dropped a few bodies on the way. He was bald too. He said, “You ain’t gotta kill no old lady like that. You just ain’t got to do it.”

Ed nodded and looked down at the table. “What I’m saying. Ain’t necessary at all.”

Kimball went on. “Little fucking psycho,” he said with real disgust. “You kill a gangster, no problem. You kill a motherfucker you got a beef with on the street, no motherfucking problem. Little old lady ain’t done nothing to you? Shit, man. I don’t know how you bunked with that little bitch.”

“I can’t stand him,” I said. “We only bunked for a little while; then I asked to have my own cell back.”

“I broke into plenty houses,” Ed said. “The people come home, all you gotta do is tie ’em up in the basement, take the shit, and leave. Nobody gotta get hurt.”

“I heard that.” Kimball crossed his arms and said, “Little punk better hope I don’t see his ass out west.”

“West” meant prison, the penitentiary. Paradise County Jail was in Thompsonville, Illinois, and Thompsonville was on the eastern edge of the state, so no matter where you went after you were sentenced, you were going west.

I thought about guys like Ed and Kimball breaking into people’s houses. I imagined them breaking into Mom and Dad’s house. I imagined them tying Mom up. The thought pissed me off. A lot of the guys in jail seemed to live that way. Armed robbers, home invaders. Seemed like they’d all done it dozens of times. And who knew what else they’d done? They’d probably been doing this shit their whole lives. That’s all they knew. Rob a house, go to jail, go west, get out, rob another house, go to jail … Jesus, I thought. All those people, all those victims … A normal person might never be the same after an experience like that, but to them, it was just all part of a day’s work. They didn’t feel anything for their victims. They didn’t particularly dislike them or want to hurt them. Sometimes the victims just got in the way. I thought about the guy I robbed, how he’d told the judge he thought I should get five years. I didn’t give a shit about him. He was just the guy by the register. If he had made a jump for my gun, I probably would have shot him. Then what? I’d have murdered a guy, for a hundred sixty bucks and a tank of gas. I probably deserved five years. Perhaps the difference between me and Ed and Kimball was that maybe I would never go back to jail, that maybe I’d never rob anyone else, never hold a gun on another person, but those guys—they were going to do this for the rest of their lives. And what about me? I was a good kid, wasn’t I? I mean, basically? Underneath it all? Once you got to know me?

I had begun to think a lot abou

t the Grand Human Invention and about what really matters to us as humans, and it seemed books were at the center of it all. There was this discussion that stretched all the way back to the origins of human consciousness and forward into an unknowable distant future. It wasn’t just in books; it was in the advancement of knowledge everywhere, the fumbling for truth that always went on with human beings. It was architecture and fashion, the evolution of cities and culture. It was wave after wave of change in everything human beings created. I began to imagine being a part of it in some way. I’d flip through the pages of my own poetry, and though most of it was clearly immature, there was obviously promise. It began to seem to me that with enough time, with enough reading, enough thought, anyone could really take part in this discussion, this advancement, this evolution.

I’d dare to imagine myself as a real artist, a real thinker. It seemed noble to me. And it seemed so possible sometimes, but other times, it seemed idiotic to even imagine myself in such a role.

And what about what I knew now, about everything, about the Invention, about life … ? Did it mean anything? Would it make a difference?

I was suddenly afraid. My heart began to beat fast and I felt a cold sweat come up. I had the feeling, a revolting feeling, that maybe I wasn’t such a basically good kid after all. Maybe I was one of those people. And maybe I would come back.

[ FORTY-FOUR ]

The day I got my last in-school suspension—the in-school suspension that ultimately led to the fire and my expulsion, my night in juvie and all that—I was sitting in math class and I couldn’t pay attention. The teacher’s name was Mr. Hallinson. About four and a half feet tall, a bald little weasel with a whiny voice. I couldn’t listen to him. His voice was driving me nuts. I couldn’t sit still. I had an impulse to move around every couple of minutes, get up and walk around the class, go to the chalkboard and write something, throw an eraser at a friend. I was like a hyperactive autistic kid. This was about two weeks after I’d run out of pills. I was losing it, and I didn’t know why, but of course it was because the shit was leaving my system. I was becoming dopamine and norepinephrine deficient.

I got up and walked to the board.

Hallinson intercepted me. “What do you think you’re doing?”

I went around him, picked up a piece of chalk, and wrote FUCK THIS CLASS on the board.

He said, his face turning red, “Erase that right now!”

I turned and said, “You do it.” I threw the eraser across the room at Rich Bass, who was laughing in the back row.

Hallinson lost his mind. He started screaming, “Get out of this class right now! Get out! Go to the office!”

Callander stared at me from his side of the desk and I slouched in my chair chewing on my lip. “What’re you doing, Nate? Thought you were all better now.”

“I did too,” I said.

“Why don’t you just drop out?” he asked.

“I can’t. My parents won’t let me.”

“That’s too bad,” he said.

I got three days of in-school suspension for disrupting math class. There’s a closet right off Callander’s office with a desk and a chair in it. That’s where you sit for three days. He gives you a list of questions, personal questions: How do your parents get along? What do you like and dislike most about school? How do you get along with your friends? You’re supposed to write ten pages of answers a day. I’d had in-school suspension before and wrote only a few pages, and that turned out to be fine. I didn’t want to write this time. I couldn’t focus. I couldn’t think.

The confines of the closet drove me insane. I walked out of there every twenty minutes and went outside to smoke. I wandered around the grounds, down to the football field, into the woods. I smoked and fretted. It was agony—the harshest, most profound frustration I’d ever felt. I leaned against the closed-up concession stand by the football field, completely disappointed in myself and the world. There just did not seem to be a way forward. I spun around and punched the wall of the concession stand. Then I held my fist and fought back the tears.

At one point during the in-school suspension, Callander brought me out of the closet into his office and said that I was being withdrawn from art class at the teacher’s request.

“My God,” I said. “Art is the only class that I work in. It’s the only class I enjoy.”

“Mrs. Indlestein says you’re a disruption.”

“I’m not a disruption in that class!”

“That’s the way it is,” he said.

This hurt. Indlestein seemed to like me. She was young and not bad-looking. I liked her. The treachery! True, she was always writing my parents. True, there was always a satanic theme to my art, but really, man—was that her place? At least I did the work!

I made it through three days of suspension. On the last day, I wrote ten pages quickly and handed them to Callander.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“The questions.”

He laughed. “I need thirty pages. This isn’t going to cut it. And if you’re in there tomorrow, it’ll be forty.”

My vision began to blur. I wanted to bash the motherfucker’s head in right there. I turned slowly and went back into the closet, shut the door behind me, and stared at the wall. I couldn’t take another day. It was already two o’clock, and there was no way in hell I could write twenty pages in two hours. I sat down and stared at the wall. I listened to that bastard go about his business. Someone was brought into his office.

I heard him say, “So what did you do this time?” Same thing he always said to me.

I heard Rich Bass’s voice. “I didn’t do anything. She says I was talking to Roger during class and I wasn’t. I hate that kid. I wouldn’t talk to him.”

Callander says, “I’ve got to call your probation officer.”

Rich says, “Come on, man! For what? I didn’t do anything.”

“Your PO said if you got in trouble one more time, Rich, I’ve got to call.”

I listened for half an hour. Eventually they left and the office was quiet. I went out and got my ten pages. I was disgusted. Fucking cocksucker. I had answered those questions honestly. I told them what I thought about Dad and why I didn’t like school. I talked about Joan and Philip and the rest of the kids I knew. I felt like an ass. Nobody deserved to know this stuff. I went back into my closet and started wadding up the sheets. By the time I was finished there was a pile of wadded-up sheets of paper on my desk, a little pyramid. I took my cigarette lighter out of my pocket, paused for a moment, then set the paper on fire. Up it went, and fast. I jumped up and left the room, passed quickly through the outer office where the receptionist sat. When sneaking out that week, I had been careful, moved slowly, and she’d never noticed me leave. This time she did. I walked out of the office and started down the hall, took my smokes out of my pocket, stuck one in my mouth, and lit it. Some girl who barely knew me passed by, gasped, and said, “What are you doing?”

I knew Joan was in home ec now. I went to the room, banged on the door. Mrs. Marsel opened the door. “Joan here?” I said.

She hesitated. “Yes.” She disappeared.

Joan came out and I took a triumphant drag from the smoke. “What the fuck are you doing?” she said.

“Fuck this place,” I said. “I did it. This is it. It’s all over.”

Just then Callander rounded the curve in the hallway and yelled, “Nathan!” I took off, ran out the door, and sprinted across the field. He stood at the door and yelled, “Nathan, come back here!”

“Fuck you!”

“Come back or I’ll call the police!”

“Fuck you! Call the fucking pigs! I don’t care!”

And with that, I disappeared into the woods.

In the woods there was an observation tower, twenty feet tall. I climbed the steps and sat at the top and smoked, thinking about what might happen. I expected the cops to come, to take me home, to tell my parents, and maybe—maybe—I’d go back to the hospital.

I waited and waited, and finally got bored. So what to do?

I made my way back out of the woods and into the elementary school. This was where the art class was held—I don’t know why. We were constantly walking back and forth across a country road from one building to another even though you’d think this was kind of dangerous. I walked to the art room. It was during my usual art period, so my class would be in there—just like old times. I slapped the door handle down and kicked it open.

I burst in like a mass murderer and said to Indlestein, “That’s right, bitch. I’m back, and there’s not a goddamned thing you can do about it.”

She was stunned. I walked to my usual seat by Heidi and sat down. I told Heidi, “I set the fucking office on fire. The cops should be here anytime.”

Her eyes widened. “No, you didn’t.”

“Yes, I did.”

I noticed Indlestein whispering in the ear of a boy next to her desk. It was the retarded kid in the class, the suck-ass. He left the room. I yelled after him, “That’s right, go tell them the juvenile fucking delinquent is here.”

Indlestein’s eyes went wide as she said, “No, no! That’s not what he’s doing. He’s just, uh, getting some more pencils.”

“Bullshit.”

“I swear he’s not going to tell anyone.”

“Well, at least I won’t have to fucking kill you, then.”

She paused. She looked afraid. She asked, “Why are you doing this?”

“Because I hate this school. I hate you. I hate the administration. Why did you betray me?”

“I—I didn’t betray you,” she stammered.

I gave her that look. Come on now!

She said, “Honestly, I didn’t.”

I lit a smoke and watched her while I smoked. Within minutes, the door opened and Callander entered with a sheriff’s deputy. The cop’s name was Maize. Everybody knew him. He was a fat old guy who’d arrested everyone I knew at one time or another. They cleared the other students and Indlestein out of the room.

I said, “See you, Indlestein, you disappointment.”

Good Behavior

Good Behavior