- Home

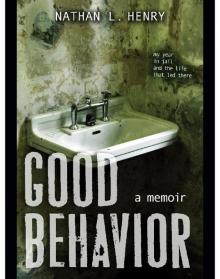

- Nathan L. Henry

Good Behavior Page 4

Good Behavior Read online

Page 4

Everyone at school picked on David, but it never seemed to bother him. He was a perpetual outsider. He was like a wild kid that someone had found roaming the woods on all fours, and then barely civilized him through severe punishment. His clothes were always filthy and stained with animal blood—the same clothes he hunted in. On the elementary school playground, if anyone ever asked me where David was, I’d say, “Look for the buzzards.” I thought this was pretty witty.

In fourth grade David would bring severed raccoon paws to school and scratch girls with the claws. There didn’t seem to be any real provocation for this. He just hated the girls. There’d be a crowd of them gathered at recess, talking, laughing; then suddenly chaos would erupt and one of the girls would go into a panic, screaming about rabies and dying. And David would run from the group waving the paw in the air like a maniac. The principal whipped him more than once for this.

I was whipped only once at school, and that was for punching another kid in second grade. I knocked the kid’s tooth out. His name was Rich Bass, and to this day he has a screw-in tooth because of me. I honestly cannot remember whether it was intentional or not. I do remember how thoughtless, how fast, blurred, chaotic things were then—running and chasing, as if I’m flying a thousand miles an hour over gravel or asphalt.

Because Dad was so paranoid, so worried, so fretful about everything—and he was fretful, the worst possibilities always occurring to him first—I wasn’t allowed to do much. Most of the time I was confined to the house. I was allowed to spend time at the Turner farm because Mom and Dad assumed I was being supervised. They assumed Gladine, being the good woman she was, kept a pretty firm grip on the actions of her six children, but she didn’t. She believed that kids who live in the country should be able to roam the countryside. They should be able to camp and hunt and fish and swim, and we did all those things. We rode horses at full gallop across the fields bareback. And it was innocent … in a sense.

David and Philip and I slaughtered wild animals for fun. I’ve still got the severed paws of a groundhog whose head I beat to mush with brass knuckles. We got high on the killing. It seemed natural. We thought it was just like what anybody else did when they went out during deer season with a rifle. We just had more passion for it, so we figured we should do it all the time.

The woods in which we did the killing were mostly barren of life by the time we were sixteen. The dogs would tree raccoons, possums, or groundhogs, and we would stone them with heavy rocks from the railroad tracks until they fell; then we’d beat them with sticks or hatchets or hammers—we seldom took guns along, at least when we were young. We hunted with unorthodox weapons, and it was tough. Unless you’re a crack shot at throwing hammers, you will never kill a squirrel with one. We once killed a groundhog with a pellet gun, shot him thirty times in the throat before I laid into him with the brass. With a hacksaw, I took my souvenirs.

One night when I was fifteen, we were camping in the horse field with great bonfires fifteen feet tall, drinking beer and smoking skunk weed through modified soda cans, and the dogs found a possum in a tree across the creek. While David had climbed the tree and was trying to beat it out with an ax handle, I impaled it with a frog gigger, which is a long pole with a spike fitted to the end, and knocked it to the ground, then pounced on it with a pocketknife. For those moments, in the frenzy of killing, I felt like the perfect predator, performing a natural and necessary function. Nothing was out of place in the world, and I was in control.

There were hundreds of such incidents. Like the time we put a possum in a fifty-gallon drum and tortured it with sharp sticks and pokers until it was seething. But torture was rare. On my sixteenth birthday, David and I went hunting with kitchen knives and a .22 rifle and we found a raccoon at the base of a walnut tree. There was a lot of brush around and the animal was trapped, so we took our time filling it with holes. Raccoons make such a terrible hissing sound while dying. That same night, a couple of miles away, we found another raccoon about twenty feet up in a tree. We could see only the reflection of our flashlight off its eye and so, naturally, that’s what we aimed for. We probably wasted fifty shots and still hadn’t made any progress when we realized that we were down to our last shell. David climbed the tree, his specialty, and began to poke at the beast with a twelve-inch butcher’s knife. The raccoon fell on top of him and then down the tree. It was scrambling down the trunk, about five feet from the ground when I took aim. I fired, but missed. It continued to advance. I spun the rifle around and brought the butt of it down onto the raccoon’s head, then again and again until there wasn’t anything left.

I would eventually, many years after all this, acquire a lot of cats, tons of cats, mostly strays, and I would lavish them with affection. I would pamper my goddamn cats. I would overidentify with them, to compensate for the horrors I visited upon the animal kingdom when I was young. It wasn’t just cats, it was all animals. One day I stopped my car in the middle of a road and leaped out, dodging fast cars and ignoring the assholes flipping me off and honking, so I could carry a giant turtle to safety, as it was obviously taking too long for it to cross. I’d save the lives of doomed raccoons trapped by exterminators. I would not be able to help myself on such occasions. I wouldn’t choose to empathize with the animals—I just had such little empathy for them when I was young that, when it came years later, it would be strong and sometimes very heavy with guilt.

[ ELEVEN ]

Flynn knocked on my cell door at five thirty in the morning. He didn’t knock very loudly—he tapped, not with his knuckles either but with the pads of his fingertips. He opened the door slowly, silencing the clank of his brass keys as much as he could, poked his face into the dark cell, and asked quietly, oh so quietly, if I wanted to go to the recreation yard or if I wanted a shower.

He was quiet for a reason. He wasn’t being considerate. He just didn’t want me to wake up. He didn’t want me to have rec or a shower. He wanted to whisper into my cell, and he wanted me to groan, and he wanted to write on my sheet that I refused rec and shower for the day. He wanted as many guys as possible to “refuse” rec and shower—it would be less work for him.

I got to leave my cell for an hour a day. One hour out of twenty-four. The rest of the time I stayed in the cage—this was my life now—and just so that Flynn could spend more time at work doing nothing, he did everything he could to cheat me out of that one hour.

“You fucking shit,” I said. “What time is it?”

Flynn huffed. “You want rec or shower or not, Henry?”

“Do I want to go outside and throw basketballs at a little hoop for half an hour before the sun has even come up, when it’s thirty degrees out, when I’ve only had four hours of sleep?”

“Yes or no?”

“I want you to come back at a reasonable hour and ask me the same fucking question, man.”

“This is your only chance, Henry. Either you take it now or you don’t go.”

“Fuck you,” I said. “I’m going to write a grievance.”

“Fuck you too,” he said. “Write your grievance.”

Flynn slammed the cell door shut and walked off to the next poor bastard who was in no shape to go out into the cold any more than I was, no shape to take a cold shower with that bastard staring at him the whole time.

He made his rounds at five thirty in the morning, as early as he could, when more guys were likely to still be out of it, more likely to refuse, and then he sat on his disgusting ass for the next five hours doing nothing. I hated the son of a bitch.

[ TWELVE ]

Brickville’s most unruly children seemed to come from one neighborhood, an old apartment complex known as the Projects, even though they weren’t technically housing projects at all. They were poor kids, and their parents didn’t seem to give a shit where they were or what they were doing. There were two or three dozen Project boys, and quite a few of them later became my friends. But for the longest time I was not on their good side, and they took every opp

ortunity to torment me.

One afternoon when I was eleven, Philip and I were out in a field a few miles from his house throwing rocks at an old hollowed-out tree when we decided to search a nearby shed. Hidden up in the loft of this small building was a duffel bag full of porn magazines. It’s really amazing how many porn magazines we used to find, and every time it was like winning the lottery.

That evening when we came out of the shed, we found ourselves surrounded by half a dozen Project boys, all armed with BB guns. They were led by Charlie Bender, who would remain the leader of that group for years to come; in fact, he’s probably still their leader. They ordered us to raise our hands, and we did. They marched us out of the field, but just before we got to the road, Charlie snickered and shot me in the ass. I yelped and began to cry as quietly as I could. I was terrified.

Charlie said, genuinely concerned, “Man, what’s wrong? We’re just fucking with you.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’ve just seen too many war movies, I guess.”

That night, back at Philip’s house, Amy was hanging around and I asked her to look at my ass. There was a group of girls who lived down the road. Their dad was an out-of-work drunk, and their mother was dead, so they were always running wild—we called them the crazy girls, because they were, or at least they seemed to be. Amy was the oldest of crazy girls, slightly younger than me, and I had a mild crush on her from the beginning, but this crush would later grow into a full-blown obsession.

“What?” she said.

“Will you look at my butt? I got shot. Tell me if I need surgery.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“Please.”

“All right.”

I unbuttoned my pants and moved them down past my ass cheek, and she examined it closely. This was incredibly thrilling. It was worth being shot in the ass to have Amy look at my ass.

“There’s a welt,” she said.

“A welt? What’s a welt?”

“A bump.”

I turned back around to face her and buttoned my pants. She had long brown hair and hazel eyes. I wanted to touch her.

“A bump?” I asked.

She laughed and said, “You’re stupid.” And she ran out of the house screaming, “STUPID! STUPID! STUPID!”

There was one Project boy who was particularly evil. His name was Random Cordero and he was a complete bastard. There was nothing redeeming about him. He was bigger than everybody and bullied anyone who wasn’t a part of his clan. One evening when I was riding my bike home from Philip and David’s house, just when I entered town, he appeared out of nowhere and began to chase me. I panicked and pedaled as fast as I could. He stayed right on my ass the whole way home.

He kept yelling, “I’m gonna get you, you fucker!”

I pedaled straight into our carport and crashed into the fence. He just kept on riding. A couple of weeks later I was fooling around under the bridge and he showed up. He didn’t say a word. He just tripped me and stepped on my chest. I was in the mud and he pressed his foot into the middle of my chest, pushing the wind out of me. I couldn’t breathe. He just grinned like a fucking psychopath. I began to panic, and just then my mother yelled for me. He let me go and I ran like hell.

Not too long after this, Random got himself a job at a Pizza Hut in Beckettstown and started dating a girl. The girl had previously been involved with a black dude, and this black dude was a mean son of a bitch. Random ran his mouth off to the guy, probably called him all sorts of racist shit, and one night when Random was taking the trash to the Dumpster, the black dude got ahold of him. It wasn’t very late in the evening and the area around Pizza Hut is pretty busy. There were lots of people around, lots of spectators. They watched this guy stomp Random to death, right there in the parking lot of Pizza Hut.

I heard about it from Random’s uncle while I delivered ads on a Sunday morning. I was disturbed inasmuch as any fatal beating will be disturbing, but to be honest, as for Random being dead, I did not feel terribly bad.

[ THIRTEEN ]

I was in P-13 for maybe a month. I grew used to being alone. I slept for as long as I needed to and was always fully rested. I read a great deal, always had a stack of books a foot and a half high by the head of my bunk. This stack of books served as an end table on which I could rest my coffee while reading. I’d read for hours and hours at a stretch. I’d finish a five-hundred-page book in just a couple of days. I even started writing poetry. It rhymed, and since I used a dictionary and a thesaurus, my vocabulary was growing exponentially. I couldn’t pronounce a huge percentage of those words because I’d never heard them spoken aloud, but I knew what they meant.

The meals were bad, but I got used to them. There’s a thin slot about two feet up from the bottom of the cell door—this slot has its own steel door on hinges, which opens outward and downward to form a kind of shelf on which the trustees set your food tray. When the guard unlocks the tray door and slams it down, it racks the cell with noise. They came with breakfast at six o’clock in the morning when I was down in P-1. In P-13 it came at around six forty-five. With oats, toast, and a hard-boiled egg, we had a choice of awful watery lukewarm milk, mixed in vats with water and dried concentrate, or coffee. I began to opt for the coffee. It was awful shit at first. I don’t know anyone who ever loved coffee from the start, but I grew to love it and began to order bags of instant coffee through commissary. I drank it constantly.

My cell overlooked the rec yard, so I’d watch my fellow inmates when they were out there. Most of them were comfortable in this environment. They ranged from young thugs to old men. Most of them had been to prison before and knew what sort of behaviors and attitudes to adopt. They puffed out their chests and strutted, sometimes pumping their fists outward for no apparent reason, as if delivering a punch. I didn’t want to go to prison with these fuckers.

My public defender, the one time I talked to him, didn’t offer any reason to be optimistic. All he would say is, “We’ll do what we can do.” Then he began to request continuance after continuance, which are postponements of trial. He told my parents that I was better off where I was, rather than home on bail, because by the time I went to trial, I would have already served a percentage of whatever was likely to be my sentence. But bail was not a possibility anyway. Besides, I had been on probation in Indiana, and there were charges against me for stealing Dad’s gun and car and skipping probation. If they bailed me out, I’d just be arrested again as soon as I got home. So either way I was screwed.

My public defender wouldn’t offer any guesses as to how much time I might get, and he didn’t give me any cause for optimism, so as far as I knew, I was eventually going to end up mixed in with those barbarians down there strutting their shit in the rec yard. It was just something I was going to face.

There’s a difference between county jail and prison. If you’ve committed a felony—like murder or armed robbery—you go to county to await your trial, and if you get a long sentence, you’re shipped off to prison. If you’ve committed a misdemeanor, maybe you’ll do a couple of months in county and that’s it. A lot of convicts who’ve been through county jail and to prison will tell you they’d rather be in prison any day of the week. You can’t smoke in county, it’s harder to smuggle dope into county, and there’s limited movement around the facility. Prison is penitentiary. Think San Quentin. Think guard towers and guards with machine guns. They house hundreds, if not thousands, of inmates. County jails usually house at most only a few hundred inmates. They’re smaller and—I’m going to guess, since the population is more transient—less corrupt when it comes to smuggling contraband, and you can’t smoke.

Prisons are huge, civilizations within themselves, and the populations are sorted out by race or by gang. If you’re used to this sort of thing and you’re a hard-core thug, maybe it’s no big deal—who knows? Maybe if I were up in a cell block with a bunch of thugs, I’d feel differently, but I wasn’t—I was kept by myself or sometimes with other juvies, and

that was fine by me. I’d rather just be left alone to read my books. But it wasn’t going to stay that way forever—when I was finally sentenced, finally convicted, I would sure as hell be sent to prison. No more books. No more quiet contemplation. Into the fucking jungle I’d go. I’d get my ass kicked, I’d get fucked in the ass, I’d get a makeshift knife in the kidney, and there I’d die. I was positive.

This threat of real prison was not easy on my parents. For the time being, they knew I was safe, but no mother wants to imagine her boy raped or beaten. And for years after all this, my dad actually left the room when the subject arose. Once I cried on the phone with Mom. I was sitting on the floor with my back against my cell door, with a knee up, middle of the day, sun streaming in through the window. A crowd of barbarians was being herded down the corridor and one of the punks unplugged my phone. The phone cord ran under the door and out into the hallway, where it connected with a jack near the floor, and some shit thought it’d be a cute thing to do to just unplug it.

I leaped to my feet and kicked and punched the door and shouted. I screamed every threat I could come up with. All I heard was that snickering—the stupid laughter only a bully can produce. I banged on the door until my hands hurt and my voice was raw. Then I collapsed, and wept.

Pretty soon Josh came by my door and said, “Your phone’s unplugged. You want me to plug it back in?”

I got up and sniffed, and said, “Yeah, thanks, man.”

Most of the time, though, I held up fine. On their way to visit me, my parents and my brother, while winding down the corridors to my cell, passed dozens of other cells, and dozens of other visitors. Dad said a lot of them turned his stomach, the way those guys whined and cried. My dad said he didn’t want to think about how other men behaved in that situation. And one time he said, “The way you’re holding yourself up, Nate”—he nodded—“I’m proud.”

Good Behavior

Good Behavior