- Home

- Nathan L. Henry

Good Behavior Page 7

Good Behavior Read online

Page 7

The preacher got up, huffed, and knocked on my cell door for a guard to let him out.

When he left I said, “Take it easy.” He didn’t respond.

I never let them in my cell after that. What a sad game it all was. They swarm us in jail, at literally the lowest point of our lives, and try to exploit that misery to make converts. The convict has zero power, and is scared to death. If he can befriend anybody who might be in a position to help him, he will.

But these preachers couldn’t help anybody. It gave them something to do, and it gave them a sense of power. They had no real power, of course. They were about the least effective people I’d ever seen. Look at Arnold, the most convincing born-again around. He’d swallowed a whole world of Jesus, and now that he was up with the apes, he was just like the rest of them, and Jesus was nowhere around.

[ TWENTY-TWO ]

The train tracks ran from the farmhouse into Brickville, right past my house—it was a two-mile hike, a passage that I often used when I skipped school or ran away from home. I was walking the tracks where there weren’t any tracks anymore, even the wooden ties had disappeared, just an elevated line of giant pieces of gravel that passed by my house and continued alongside a little creek with no name, straight past the park and baseball diamonds and basketball courts where the old ominous four-story nineteenth-century redbrick school building used to stand, out on the north end of town, and out into the woods and through and above cornfields and soybean fields, right over the creek by the farmhouse on the old iron trestle, a skeleton of a structure with gaps in the iron girders that looked down twenty feet to the water.

It was a hot midsummer day; I was fourteen years old, almost fifteen, and I walked past the ball diamonds. The place was packed with people. There were games going on, kids running around, adults drinking beer and yelling shit at their children on the field. “Get the fucking ball, you little cocksucker, before I take you home and beat your ass!”

I was wearing a dark green knee-length WWII army overcoat with the shoulder insignia of an artillery man, a baseball-style camouflage military cap with the visor pulled down just over my eyes. My hands were in my pockets and I was holding the coat closed. Each hand, concealed in the deep pockets, clutched the grip of a pistol—in my left was a .25 automatic with a six-shot clip and in my right was a .380 automatic with a seven-shot clip. If I were to let my coat fall open, two .22 revolvers, one black and the other gold, would be visible stuffed into my waistband, no doubt a bit shocking to all those barbarian dipshits I was walking past.

Additional firepower and killing devices: a .32 derringer in my left boot and a .410 shotgun slung by a leather strap over my right shoulder, also concealed under the long, heavy coat. I suppose if someone looked closely, they would have been able to see the barrel poking down beneath the hem of my coat. On my belt were pouches full of extra ammunition and two large hunting knives, one serrated and one not, their blades seven or eight inches long. All the weapons except for the serrated knife and the shotgun belonged to my father.

I walked quickly though the park, getting a few looks and one or two pointing fingers. One redneck even yelled, “Hey, boy, you going to war?” and all his cohorts laughed like fucking buffoons. I considered right then just dropping the coat and filling them all with holes, but I kept walking, without looking back.

That was the first time I ran away. My brother showed up at the farmhouse on his motorcycle two hours after I got there and found Philip and me shooting at cans in the creek. He had discovered my escape, had checked my father’s gun collection and come out to retrieve me. He took me home and I put the guns away—he didn’t try to shame me, didn’t really say much at all, but just looked very serious and disturbed. I don’t think he had any idea at all what to say to me.

I started wearing my hair longer, bangs down over my eyes, with pocket T-shirts and jeans, and I started slouching. I smoked in the woods by the school with Rich Bass and Charlie Bender—Charlie had become a badass, a real badass nobody fucked with.

Rich said, “Shit, Nate, you smoke?”

“Fuck yeah, I smoke.” I didn’t inhale, though.

Charlie said, “You’re all right, man.”

And from then on … I went with it. Knocked people out when they stood too close or looked at me wrong. I put blood on the hallways, made jokes that weren’t really jokes about burning down the school, about killing the teachers, about machine-gunning kids. I said Satan was my master, Satan wanted me to kill … and they all backed way the hell off.

This was an epiphany. It came like a revelation.

I said to Philip one day, “You can’t be a part of the in-crowd because you can’t afford the clothes. As it stands you can’t make fucking jokes in class because those cunts make fun of you. It’s like you’re not allowed to participate in society. They got a lock on it all. You can’t play their game because they’ve got it rigged. Well, fuck them and their fucking game. Stay on the outside. Make ’em afraid. Be dangerous, right? Be beyond it all. It’s easy. Just be willing to do whatever it takes. Be willing to be scarier than the next guy.”

“Fucking A!” Philip smacked his fist into the palm of his other hand.

I started ticking off the tenets of my new lifestyle: “Satanism, anarchy, black leather, heavy metal, chains, barbarian jewelry, ripped-up jeans. Always be armed, with the brass knuckles and the blades. Steal, fight, terrorize … be willing, man—that’s all it takes. Be willing to inspire fear, and fuck up anybody who gets in your way.”

And that’s what I did.

Few things are scarier than an apparently homicidal Satan worshipper. Philip became as infatuated with witchcraft as I was. We aspired to be, in our own words, warlocks, absolute evil with absolute power. We believed in magic, the power of spells—if the book said you had to dig up the skull of a dead five-year-old child, grind it to powder, and mix it with two parts goat milk and one part your own blood in order to see the future, we were looking for the most secluded cemetery to rob. Philip said he knew of one in Kentucky, a very old cemetery from the seventeen or eighteen hundreds on his grandparents’ property, where no one would see us. We never made the trip—neither of us had a car and neither of us had money.

Philip threw down the last tarot card and said solemnly, “Nate, you are not going to die young. You’ll get a job in a factory and have a miserable ugly wife and disgusting kids and you’ll blow your head off with a 12-gauge when you’re fifty.”

I just looked at him.

“I’m serious.” He threw up his hands. “It’s in the fucking cards, man!”

“Fuck you. It’s not in the goddamn cards. You’re misinterpreting them.”

“I’m not misinterpreting shit, man. Look, right there, the guy with the cups—over here, the death card …”

I started to gather up the cards.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“They’re my cards, man. When you know what you’re fucking doing, I’ll let you read them.”

One time when I spent the night with Philip and David, Philip got caught stealing cigarettes from his dad and the old fucker came up to his room and knocked the piss out of him right in front of me. Philip and I conspired that night to liberate ourselves. This was our plan: We sneak out the upstairs window around three a.m., when everyone’s asleep, climb down the side of the house on a metal structure that was used to support a huge television antenna, walk the tracks all the way to Shoshone, a town even smaller than Brickville, about ten miles away. There we’d get a friend to drive us to Lake Town in the north of the state, where a guy I had met through some friends in another small town a couple of miles from Brickville lived. This guy was in with the Lake Town chapter of a major gang (of which he was probably the only local member—but we imagined it to be a whole secret army). We’d join up and either sell enough drugs or get involved in enough capers to finance a trip to California, where we’d join the Church of Satan.

That night we walked ten miles in six

inches of snow, freezing the whole way. There was a full moon, and with all the light reflecting off the snow, it was clear as day and dead silent. We trudged on and discussed our plans. Philip was ecstatic. He hugged me numerous times, told me he loved me. About three hours into the hike, it began to snow again, but by now we were well past Brickville and only an hour or so from our destination. We hid out for a while in an old barn, afraid that if we fell asleep, we’d freeze to death.

It was too early to knock on anybody’s door. The kid still lived with his parents, and parents generally regard with suspicion two hoods who show up at their door in the wee hours of the morning.

“We could build a fire,” Philip said.

“Somebody might see us. Call the cops.”

“Yeah.”

“Just think of California, man. Sunshine. Hot-ass girls.”

“I’m still cold.” He shivered.

“Me too.”

We put it off for as long as we could, but when we got too cold, too exhausted, and too hungry, we had to bite the bullet. We had to get inside. After tapping at the kid’s bedroom window for about fifteen minutes, unable to wake him, we finally went to the front door and rang the bell. When his mother answered the door in her nightgown and robe, we made up a story about my mom dropping us off on her way to work. Our friend, who had been sleeping soundly in a warm bed all night, the only friend we had who owned a vehicle, our only chance at escape, came to the door with sleepy eyes.

“What are you guys doing?” he asked.

I said, “We’re going to California, man.”

“To join the Church of Satan,” Philip added.

“Are you nuts?”

“No,” I said. “We need you to drive us to Lake Town.”

“You are nuts.”

“Come on, man.” I punched him in the shoulder. “What else have you got to do today?”

“Not go to Lake Town,” he said. “I’ll give you a ride home, but that’s it.”

While he got dressed, Philip and I waited by the door.

“This is bullshit,” Philip said.

“I know.”

In the truck, I said, “Man, it’s only, what, two hours away?”

Then, rather emphatically, our friend said, “I’m taking you home. I am not driving to Lake Town.”

“Okay,” I said. “Don’t get pissed.”

“Yeah, Jesus,” Philip said. “It’s no big deal. Let’s go home.”

[ TWENTY-THREE ]

In P-14, the cell next to mine, was a young wiry black guy named Timmon. I don’t know what he was in for, maybe assault and battery—no, probably burglary; he was too much of a pussy for assault and battery. He was loud and a moron and he needed the radio on twenty-four hours a day.

There were little speakers in the corridors outside our cells through which the guards would pipe music. Generally it was from a classic rock radio station, but sometimes it was country. It all depended who was in Control that day. Control was a room behind mirrored glass down by Sallyport where they have a panel of video monitors to observe all the parts of the jail. Every corridor and every cell block had a camera in it. Control controlled everything, even the radio station.

The guards would turn the speakers on and off if you asked them. Timmon liked to eat with the radio on, shit with it on, even sleep with it on. I’d ask a guard to turn the damn thing off and immediately Timmon would be banging on his fucking door screaming like a retard because he couldn’t stand the silence. There was no peace. At first Timmon and I got along. He even traded me a cigarette for some magazines one time—the first cigarette I’d had in six months. But those were the good old days—back when Timmon wasn’t driving me nuts with that fucking radio.

One day, Josh walked by and I said, “Dude, will you please turn that speaker off? I can’t stand it.” So he did.

Timmon went crazy, started kicking his door.

I looked at Josh and said, “Walk away, man. Please, just walk away.” So he did.

Timmon yelled to me, “I’ll kick your fucking ass, you little motherfucker.”

I yelled back, “Listen up, cocksucker. I’ll gut you like a fucking groundhog if you don’t shut the fuck up!”

“What?” he said. “You’ll gut me like a groundhog? What are you, some kind of backwoods redneck? Fuck you, cracker! I want the radio back!” And he started kicking his door again.

I yelled, “Timmon, sit down and shut up!”

“Fuck you, cracker!”

So because this was the second time he called me a cracker, which is a racial slur in itself, I felt it only appropriate to respond with, “All right, nigger, I’m cutting your motherfucking throat.”

“Whoa!” Timmon yelled, out of his mind now. “You call me a nigger, white boy? You think you can call me a nigger and live?”

“How many times do you expect to call me a cracker and not be called a nigger? Think about it, retard.”

“That’s it. When these doors open, I’m coming in there. It’s on, motherfucker.”

“Okay,” I said. “It’s on, then.”

Then, miraculously, Timmon quieted down, and I went to sleep.

Later that evening I was awakened by Leonard at my door. He was pushing a mop bucket. “You wanna clean your cell, Henry?”

“No,” I said.

“You sure?”

“Yeah.” I just wanted to sleep. Then I heard Timmon in the hallway.

“Fuck no, he don’t want you to open that door. He knows I’ll kick his fucking ass.”

Shit. I had forgotten. So I got up and pulled my sweatpants on. Leonard opened the door and I went out, stood a few feet in front of Timmon, who was several inches taller than me. I threw my hands up and said, “Okay, let’s go.”

There was a tense moment when I waited for him to strike, but then he broke out into laughter and said, “Shit, boy, you’re fucking crazy,” and went to mopping his own cell.

So I went back into my cell, Leonard closed and locked the door behind me, and I went back to sleep. That was the closest I ever came to actually being in a fight in jail, and I suppose it wasn’t much. Timmon was at least a bit less obsessed with the radio after that. Which was nice, finally.

I thought a lot about the Timmon incident afterward. I knew that when I went to prison, they weren’t going to back down. I hadn’t expected Timmon to back down. I didn’t want to fight him. I didn’t want it on my record, but I had to take the challenge. I’d seen enough prison movies to know that you never, under any circumstances, back down from a fight. Never show any weakness. I had been weak with Arnold. Having backed down from Arnold in the beginning, allowing him to torment me with the whistling—it bothered me. It made me doubt myself.

I was trying to prepare myself for prison. I was trying to get myself sharp. I didn’t know how to do that, other than to accept that everything was expendable, especially physical health. This is hard to do. It’s terrifying. I was a scrawny kid, a hundred and thirty pounds, five foot seven. I didn’t have any tattoos at the time. I looked like a boy. Compared to most of those apes I saw in the rec yard, I knew I was a victim waiting to happen, fresh meat. So I had decided that when I went to prison, I would carry a finely sharpened pencil with me at all times, and the first big cocksucker who got in front of me was getting stabbed in the throat. That was the only way I could see to establish any kind of threatening presence. This of course meant a murder rap on top of the robbery rap and possibly life in prison. But life in prison with the reputation of a killer might be a whole lot better than fourteen years of torture.

[ TWENTY-FOUR ]

I remember standing in my brother’s room, leaning against his door while he fiddled with something, perhaps worked on the final stages of building a sword—he was always making swords and daggers and billy clubs, and we’d often sword fight in the alley beside our house—and as I was standing there watching him do this, I tried to express to him my great fascination with crime. Thanks to my dad, I had always had a steady

dose in the form of movies about gangsters and thieves of all kinds.

I said, “Man, I want to be like Al Capone. I want to be like Dillinger, man, wanted by the FBI and on the run. I want a rap sheet a foot thick: public enemy number one.”

My brother nodded and occasionally looked up and said something only minutely discouraging, but really he was just listening.

“What about prison?” he finally asked.

“They all went to prison at some point, or were killed. That’s just part of the game.” I shrugged. “Do some time if you have to. No big deal. But to have done all of those things! That’s the point.”

And indeed that was the point. To have done. I was more interested in having an interesting history than in carrying out the acts themselves.

This had been true with my fascination with all things military as well. When I was forming the Black Hawks, I had visions of becoming a fascist leader, of clawing my way to the top by ruthless means. I desperately wanted to be a Hitler or a Stalin, and if that wasn’t possible, then I wanted to be a leader of organized crime. I saw myself at rallies moving tens of thousands to rapture by the passion of my speech.

Philip and I would engage in small-time criminal acts, like breaking into abandoned houses or stealing cigarettes from the carryout next door to my house. One night he and David and I, decked out in our mercenary uniforms, black face paint and all, made our way into town. We slashed the tires on a car owned by a guy who owed money to a guy David knew, and we busted out the windows in the mayor’s garage. We were chased through the streets by somebody who happened to drive by and see us—he didn’t see us slash the tires or bust the windows, but he saw us crouching beside someone’s trailer afterward regaining our breath. We split up and ran in different directions.

I was the one he caught up to. Completely out of breath after a ten-minute sprint, I gasped and heaved in the shadows behind a church. He pulled his car directly in front of me, said, “What’s going on?”

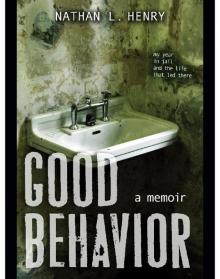

Good Behavior

Good Behavior