- Home

- Nathan L. Henry

Good Behavior Page 8

Good Behavior Read online

Page 8

“Nothing.” I was still out of breath.

“What were you guys doing back there?”

“Halloween prank,” I said. I considered bashing the guy in the face and running, but I was too weak.

He looked at me for a long moment, apparently realizing there wasn’t much he could do.

“Okay, I’ll tell them.” He drove away. Tell who? Maybe the people who lived in the trailer we were crouching beside. I don’t know.

I was bleeding. I had used the handle of a knife to shatter those windows, and a shard of glass had penetrated my leather half-gloves and sliced my right middle finger down to the bone. When David and Philip and I finally met up at our rendezvous, I peeled the glove off while David shined a flashlight and saw that my hand was covered with blood. I felt weak. There was so much blood, and it continued to drip from my fingers at such a rate that I was afraid I was going to bleed to death.

The trip back to the farmhouse was long and slow, but I made it, and managed to stop the bleeding with gauze and a bandage.

And we stole a lot. I spent a great deal of time hanging around the carryout beside our house. I knew the woman who worked there and she liked me, so I’m sure that she was quite torn when she discovered that she was missing five cartons’ worth of individual packs of cigarettes after Philip and I had spent an hour there. But she never said anything. Every time she’d look away, we’d pocket two or three packs. At night, at the farmhouse, we opened the duffel bag to show our loot to David. He was amazed and thoroughly impressed. Fifty packs in an hour each. What a fucking score. Sure, they were all different brands, most of them generic, but nonetheless, even if we had to divvy them up three ways, we would be fully stocked for weeks.

Every year at school, the sophomore band members would sell candy bars to raise money for their cause, whatever the hell that was—new uniforms perhaps. So suddenly there were hundreds of boxes of candy bars floating around the school, going for a dollar each. David and I decided that we couldn’t let this opportunity pass, so we began to break into the sophomores’ lockers. Those lockers are normally pretty secure, but then again, I had perfected my lock-picking abilities in pursuit of my dad’s porn, which he kept locked away in his den. We accumulated several boxes of candy bars and began to sell them to students at fifty cents a pop—we made a killing. But soon enough, our names got to the principal and we knew that we were about to be rounded up. David and I were no strangers to the principal’s office. I was usually sent there a couple of times a week for some kind of disturbance. Later, in the next year or two, those visits would become more frequent, and I would end up there every day for one reason or another. But this time, before the gestapo came for us, we came up with a plan. We had to unload the remaining boxes of evidence, and there were still several boxes.

There was a kid named Jeremy Sproggs who we’d always hated. Why we hated him is not entirely clear. He was not a likable kid—in fact he punched me once for no good reason in fifth grade, but I was not one to hold a grudge for something like that for four years. Perhaps he was just an easy mark, and since he was not well liked, he would make a decent patsy. So we broke into his locker and hid the boxes beneath some jackets.

We were sitting in the principal’s office and he was trying to intimidate us, talking about calling the sheriff, threatening to charge us with theft. We could both be expelled and incarcerated, he said. My arms were crossed and my legs were kicked out and I even yawned a couple of times—I was as cool as I could be, totally unbothered. David exhibited the same gangster imperturbability. When the principal finished his spiel, he asked me, “So, where is the candy?” I said I didn’t know.

“I have no idea why you suspect me of knowing,” I said. “I haven’t seen any stolen candy, but I have heard about it. Everyone’s heard about it.”

“You’re saying you don’t know anything about this?”

I stared at him for a few moments, pretending to deliberate. “There are rumors,” I finally said. “I’ve heard a name, but I’m not sure I want to tell you the name I’ve heard. I’m not a rat, man.”

“Well.” Mr. Callander sighed. “You guys are the prime suspects right now. Everything points to you.”

Now it was David’s turn. “Look,” he said. “I’ll tell you what we know if you promise not to tell anybody that we told you. If people find out that I gave you a name …” And David shook his head like he didn’t even want to imagine the consequences.

The principal put his hands together and leaned on his desk. I’m sure he wasn’t taken in by this, but he was going along nonetheless. “Okay,” he said. “It’ll be between us.”

“Okay.” David pretended that moral conflict was tearing him to pieces. He swallowed hard and glanced at me. I shrugged like it was out of my hands. He then looked back at the principal. “Jeremy Sproggs,” he said. “We heard that Jeremy was the one who stole the candy and that he keeps it in his locker.”

So poor Jeremy, unsuspecting of his fate, probably sat in math class struggling over a problem, nothing further from his mind than the possibility of being framed for a crime he didn’t commit—as far as I know he never committed any crimes, got decent grades, and aside from that punching incident in fifth grade, never caused any trouble at all. When those bastards were finished with Jeremy’s locker, his things were strewn about the hall like it was the scene of a natural disaster. And there was the candy, right in the bottom of his locker. They took photographs for evidence. And that poor bastard was expelled on twenty counts of theft, one per box of candy, his high school record forever marred by a shameful act he didn’t commit.

If I ever meet Jeremy again, I’ll apologize to him, and hopefully he won’t punch me too hard a second time.

When I was fifteen, I got hold of a book called Say You Love Satan. It was the true story of a teenager in New York who’d stabbed another kid to death in what looked like a ritual sacrifice. This is why the book sold so well—nice and sensational. Of course when you read the thing, you see that it doesn’t look like a ritual sacrifice at all. It looks like a fucked-up kid whacked out on hallucinogens getting caught up in the moment and making a terrible mistake. Happens all the time.

It was a thick book, a few hundred pages. I read the thing over and over. I carried it everywhere. It became my bible. I modeled myself after the lead character, Ricky Kasso. I occasionally asked myself, “What would Ricky do?”

I stopped working in school. I slept or read my book in most of my classes and got suspended whenever I could. If the kids at school weren’t afraid of me before, this Satanism kick really pushed it across the line. I was in the principal’s office every other day. I had completely given up. Graduating was no longer a possibility, but my parents would never agree to let me drop out, so my plan was simply to wait it out. As soon as I was eighteen, I’d leave school, hitchhike to LA, and live on the streets. There’s a Guns N’ Roses song called “Nightrain” that sums up what I wanted to do perfectly. The lyrics are all about getting fucked up and staying fucked up. That was all I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I always imagined I’d be screwing some bimbo who had a job, and she’d pay for everything. I imagined getting up late in the afternoon, taking some speed to get going, drinking and doing coke all night, and then taking some downers to sleep, waking up twelve hours later with some speed, and the cycle continues.

At my last parent-teacher conference, Mr. Simpson, my history teacher, asked me what I thought I’d be doing in five years. I said, “Living on the streets in LA.”

My mom hit me in the arm and said, “Seriously.”

I said, “Okay, seriously. I imagine myself as a janitor in a fast-food restaurant.”

She just shook her head, very disappointed.

[ TWENTY-FIVE ]

Kline came by and kicked my cell door. He said, “We just got another juvie in.”

I went to the door and leaned against the jamb. “Oh, yeah? What’d he do?”

Kline shook his head. “He’s

charged with murder.”

“Holy fuck,” I said. “Who’d he kill?”

Kline said, “I didn’t say he killed anybody, I said he was charged with murder.”

“All right,” I said, “then who is he charged with murdering?”

Kline shook his head and made a snarl of disgust. “An old lady,” he said. “In her own home. Strangled to death. You want him for a cellmate?”

“I don’t know, man. Let me think about it.”

“All right, you’ll meet him tomorrow; you’ll go to rec together. Just let us know.”

Then he kicked my door again and walked away.

I sat back down on my bunk to mull it over. A killer. An old-lady killer. Wow, I thought. A real murderer. I thought a lot about it that night, but I didn’t know what to think about it. The variables were numerous. I imagined a hard and mean kid, a criminal so tough and crude he’d make me and all my former cellmates, including Arnold, look like a bunch of pussies, a cold-blooded predator with nothing to lose. I imagined him shanking me in my sleep and fucking my dead body.

But the next day, when it came time for rec, Josh came by and unlocked my door and there the killer was, standing in the hallway, a well-groomed white kid with freshly scrubbed skin and not a hint of facial hair. He looked like he hadn’t yet reached puberty. I nodded and he smiled back—not a malicious smile, but a rather polite smile. I walked behind Josh as we headed down the corridor toward the elevator, and this kid moved up beside me, asked me what I was in for. He asked it in a real phony old-gangster-movie kind of way, like he was imitating James Cagney, but he wasn’t making a joke, just putting on a show.

“Armed robbery,” I said. And just to be polite, “You?”

“Murder.” When he said this there was a smirk on his face, like he knew the word carried a lot of weight, like he knew it would make him look tough, something he’d obviously never been.

We shot some hoops in the yard and I asked him about his crime. He said he was innocent. He said his buddy was the one who did it. He wasn’t convincing, but he didn’t exactly seem to be lying. There was just something very young and pretentious about him. I sized him up almost immediately as a pussy, whether he’d killed somebody or not.

There are subtle ways guys assert dominance and establish their status. After dealing with Arnold and Mo, and after watching the absurd monkey drama play itself out in the rec yard every day from my window in P-13, I knew a thing or two more than I used to. And I had always been pretty good at it, when I needed to be.

Subtle things. Not laughing at the other guy’s little jokes. If he makes little jokes that are naturally uttered for his own amusement, that’s one thing. Jokes intended to please others, that just cry out for approval, for laughter—those are an entirely different matter. It’s a sign of weakness. If there’s a point in a game where it’s not clear whose turn it is, you take the turn. If you both come to a doorway at the same time, you go ahead and walk through first, pretend they don’t exist. Occasionally ask pointed questions without a hint of real curiosity, and when they ask you questions, sometimes you answer and sometimes you don’t. If you do, you do it with as few words as possible.

It’s pretty easy after a few minutes to see where they stand. The old-lady killer deferred constantly, made jokes over and over again and asked all kinds of questions. He was no threat at all, just a kid, didn’t even have a firm grasp on what he was facing, what was happening to him, so after rec, I told Josh I’d go ahead and bunk with him.

[ TWENTY-SIX ]

I caught Billy between the two sets of double doors at the entrance to the high school and threw him up against a wall. He had called me a pussy and spit at me from aboard his school bus at the end of the day before. I tried to board the bus—would’ve settled the matter then, but the driver shut the door on me and threatened to call the principal. Now I punched him in the face with both fists, one after the other; when he lifted his arms to shield his face, I punched him in the stomach; when he lowered his arms, I went back to work on his face. It went on like that for a couple of minutes, until he wasn’t standing up anymore.

As far as I was concerned, I had become the super-hoodlum. I had it down, from the clothes to the walk to the bored and surly expression.

Nate, would you mind doing us a favor? Just for a minute or two; it won’t take long. Thank you, Nate; we’re very grateful. Go stand out there, right there for a minute. Look at me. Stand up straight. Just let your hands hang to your sides.

Let’s have a look at you. Long hair—not too long but long enough—bangs in your eyes, hair on the back of your head down past your collar. Head cocked back defiantly—looks like you want to kick our asses, like you just don’t give a damn. About half a dozen necklaces: silver chains, a choker, a giant Anarchy symbol medallion on a leather bootlace. A black leather motorcycle jacket, a black concert T-shirt.

What does your shirt say, Nate? Open up your jacket a little bit. There. Thank you. Metallica, Ride the Lightning. I suspected as much. Tight black jeans, a black leather wallet with three different chains connecting it to your belt. What’s your belt buckle look like? I see, a bull’s skull with red glass eyes. Black leather biker boots with nickel-plated rings on both sides, leather straps connecting them. What’s that, Nate? Oh, yes, they’re called harness boots. And I see you’ve applied some chains to your boots as well, and are those spurs? You have spurs on your boots? Why in the world would you need spurs on your boots, man? You haven’t ridden a horse in years. They’re what? I see. You could slash someone’s throat open with them, if you could kick that high. And back to the jewelry—why don’t you lift the sleeves of your jacket up. Let’s see how many bracelets you have on. My God, man, I’m surprised you can lift your arms with all that metal around your wrists. Oh, they give your fists more weight when you have to punch someone. Well, that makes sense. Do you have to punch people a lot? Suspended three times this year for assault. Hmm. Well, it’s a mystery to me why you’re still on the street with a temper like that.

What have you got in your pockets? Go ahead and empty your pockets. Don’t worry; we’re not going to confiscate anything. We just want to see. I’ll bet anything you’ve got at least one kind of deadly weapon. Unbelievable. Do you realize that if a policeman searched you he could arrest you for having things like that? You don’t care. Pair of brass knuckles, a leather blackjack, a switchblade knife—is that really a switchblade? You ever use it? Not yet. But you will if you have to. This town has a population of something like a thousand people, man. It’s not New York or Los Angeles, where someone might actually need protection, where someone encounters danger on a daily basis. You’re probably the only real danger that people around here ever encounter. Do you know that? And what do you think about that? What’s that? Fuck them? Okay, well, thank you for your time, Nate. You can go now.

[ TWENTY-SEVEN ]

The old-lady killer’s name was Dicky. He strangled a seventy-seven-year-old woman with a phone cord in her own home. We were cellmates for only a couple of weeks. I just couldn’t take it.

Dicky was effeminate and prissy, and he would surely be raped mercilessly in prison. Dicky’s life might very well end the moment he got to prison. But he was so immature, I don’t think he ever worried about his future. It was all sort of a game to him, this time in jail just some extended holiday, like summer camp. He maintained his innocence about the grandma killing as long as I knew him. He said he was hiding while his friend committed the actual murder. He could have been telling the truth—I don’t know.

Let me tell you a little bit about Dicky. Dicky walked like a bitch. He talked like a bitch: a somewhat high-pitched lilting voice, and if he didn’t actually have a lisp, he was dangerously close to having one. His concerns were bitches’ concerns.

When I first met Dicky, he had more toiletries than any inmate I ever saw. I had a toothbrush, some soap, and a towel—some shampoo too. On top of what I had, which is what every inmate had, which is what they’d

give you for free if you didn’t buy anything from commissary, Dicky had hairspray, deodorant, mousse, two or three different brands of toothpaste, an arsenal of brushes and combs, hand lotion, foot cream, facial cream, moisturizing body lotion—you name it, he fucking had it.

I’d been writing poetry for a while. When Dicky met me, he started writing poetry too, but his poems were shitty and emotional—if I would have described my own work as bricks and razors and whiskey bottles, I’d have described his as melted ice cream and deflated birthday balloons. I thought he was a moron. He had no balls.

I’m not saying I necessarily thought Dicky was gay, and even if I did think he was gay, that wouldn’t have been the only reason he drove me nuts. It was the totality of Dicky that annoyed me. It was his preening, effeminate, undermining viciousness. It was everything.

I didn’t hate gays for being gay anymore. I had hated them when I was younger—I didn’t know why. I had thought they were naturally detestable, inherently wrong. I didn’t think I needed a reason. I’d hated blacks too.

When I first got to jail, I got a book off the library cart—I can’t remember what it was, one of the first books I tried to read in there. Within the first couple of pages, I came upon a scene where a couple of guys pull over to the side of a dark country road to take a piss, and as the one guy was pissing, the other guy was watching him. The guy who was watching got a hard-on when he saw the other guy’s dick. I almost vomited when I read that. I threw the book across my cell and couldn’t touch it or look at it for a few days. I tossed a T-shirt over it so I wouldn’t have to see it. It seemed diseased and I felt that perhaps I had contracted something from reading it. I felt that I had been violated. I feared that I’d been infected.

Since that time, I have found that I absolutely love the writers Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Arthur Rimbaud. With the exception of Kerouac, they were all gay, and even Jack fucked around with his male friends. Hell, there is even good reason to believe Jim Morrison was bisexual.

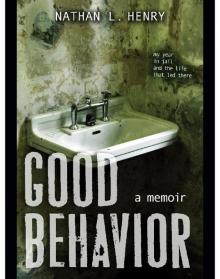

Good Behavior

Good Behavior